THE USE OF ART AS FORCE

Shirin Barghi's "Last Words," 2014-2015

It was 1861, a time of unthinkable national fracture. Frederick Douglass stood before an angry crowd at Tremont Temple, the integrated church one block from Boston Commons, and made an audacious claim. He said that art could play a role in the abolition of slavery.

From the famed abolitionist and volcanic orator who said, “it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, the earthquake… the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed (1) ,” his views on art must have seemed irrelevant compared to the issues at hand.

In her beautiful book, The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure and the Search for Mastery, Sarah Lewis (2014) puts it like this.

…Frederick Douglas was sure, even in the face of war, that the transportive, emancipatory force of “pictures” and the expanded, imaginary visions they inspire, was the way to move toward what seemed impossible.... An encounter with pictures that moves us, those in the world, and the ones it creates in the mind, has a double-barreled power to convey humanity as it is, and, through the power of the imagination, to ignite an inner vision of life as it could be. p.90

More than a century before Susan Sontag wrote about the power of photography to educate and enlighten, before Diego Rivera painted his anti-capitalist murals, and before those first awe-inspiring photographs taken from Apollo 8 forever changed our view of planet earth, Douglass lauded vision and imagination over reason. He believed that authentic representations of Black folk, whether through jazz, poetry or portraiture enabled the criticism of slavery. He hoped that one day a scholar would study “the influence of pictures on our thoughts.” (2)

To illustrate his point, Lewis (2014) recounts the path of Charles Black Jr., a good ol’ boy and jazz aficionado from Austin, Texas. In 1931, in a local speak easy, Black hears Louis Armstrong play the trumpet for the first time. At this “witness to genius,” he goes into a trance-like state. He says it “opened my eyes wide and put me a choice.” His choice—to keep a small (racist) view of humanity, or to open up. Black would go on to join the legal team for Brown v. Board of Education and play an important role in the Supreme Court’s judgment against segregation.

Sarah Lewis (2014) calls this power aesthetic force, and it can come from any form of art. It leaves us “changed—stunned, dazzled and knocked out.” p.92

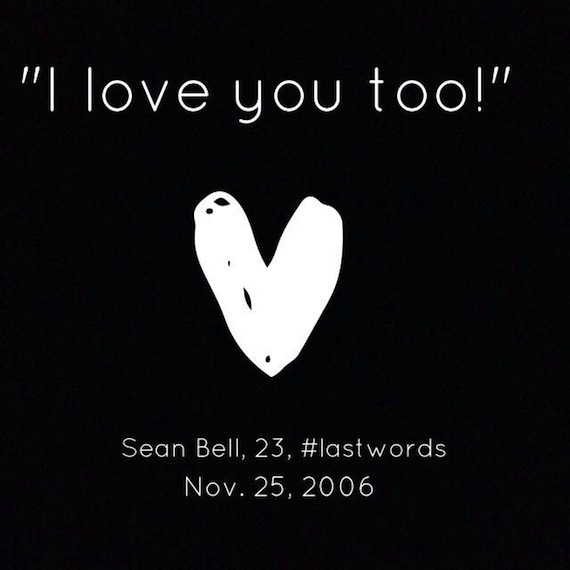

Sadly, Douglass’ 19th century prophecy has not quite come to pass. The force of art, be it music, poetry or pictures has not prevented the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Walter Scott, or Freddie Gray, to name just a few. Art has not fixed the disparities in wealth, education, and rates of incarceration in this country; it has not forced employers to pay equally or police officers to allow Black folks to go about their business unharmed. No, art has not eradicated racism or created a just society. How I wish aesthetic force could alter minds and lives as swiftly and decisively as bullets can destroy them.

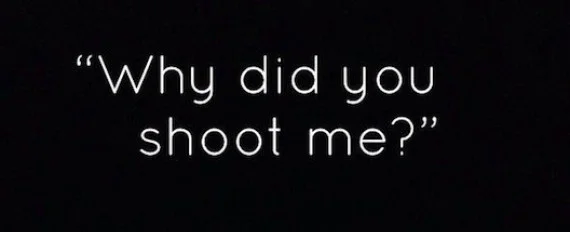

The artistic response to the brutal killings of innocent African Americans has been powerful and varied. Of what I’ve seen, Shirin Barghi’s “Last Words,” (seen above and below) hit me hardest with its truth, indeed left me stunned and knocked out. Whether or not the meme, communicated through tweets, should be considered a valid art form is not the point here. The brutal aesthetic force of this piece has the power to hit like a hurricane and does indeed leave the hypocrisy of a nation exposed.

It may not change the world, but it makes us weep for what we’re missing.

Citations

1) Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?: An Address delivered in Rochester New York, on July 5, 1852,” The Frederick Douglass Papers,” ser 1, vol 2, ed John Blassingame (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 37.

2) Frederick Douglass, “Pictures and Progress,” The Frederick Douglass Papers,” The Frederick Douglass Papers,” ser 1, vol 3, ed John Blassingame (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 461.